It all started in the mid-80s with the introduction of the Compact Disc. The digital format allowed audio engineers to push the overall loudness of their music further and further using post-processing techniques that wouldn’t have worked in the realm of analog tape and vinyl.

As these techniques improved, the Loudness Wars began. Through the ‘90s and into the first decade of the 2000s, labels encouraged engineers to push their tracks louder and louder with the idea that loud tracks capture listener attention. It wasn’t until the 2010s that the backlash began, and people like mastering engineer Ian Shepherd started to work on raising awareness on the loss of fidelity the Loudness Wars were creating.

This article will dive into the history of the Loudness Wars and where we are today.

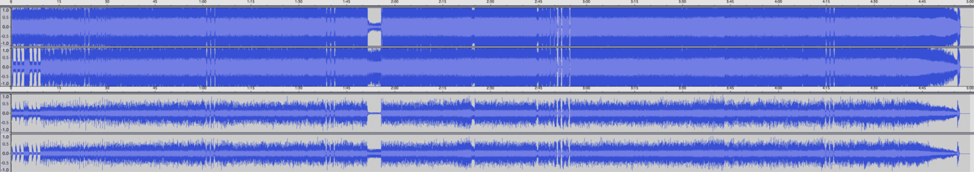

The difference in compression between Metallica's “Death Magnetic”: CD release on top vs. Guitar Hero release on the bottom.

Loudness Backlash

Why the backlash? The loss of dynamic range. Audio is made up of peaks and valleys. The peaks usually represent things like drums: high transient signals that dominate the range of volume available on the medium.

If you think about audio volume on a scale from 0-100, a snare drum hit is going to start at 100 and then quickly fade down to 0. A guitar might hit at 75 and sustain around 50 before tapering off to 0. Each instrument has a range of volume it inhabits when recorded, and the interactions of those ranges are how a song or album is mixed.

This is what dynamic range is referring to: the diversity of volume changes that occur throughout the playback of a song and album. Nature itself, the sounds that reach our ears in real life, have a pretty wide range of dynamics.

To get those big, loud tracks the engineers were pushing for, they had to start shaving off the peaks to get the whole tracks slammed up against the ceiling of maximum volume. As you do that, you sacrifice dynamic range and, as many engineers and audiophiles would argue, fidelity. Audiophiles LOVE dynamic range. They’ll constantly seek out the most dynamic versions of a recording because the idea is that it’s closest to reality, and they have the gear to pull all those nuances out of the recording.

These days we have a mix of approaches to loudness in music. Skrillex is still slamming his recordings at -6 LKFS (more on that later), while other artists are daring to not overcook their tracks and keeping things more dynamic.

Skrillex - Fuji Opener (feat. Alvin Risk) [Official Audio]

Loudness in TV Commercials

So that term: LKFS. We’re going to get to that, but first we need to take a trip through the Loudness Wars that happened in television.

Commercials are made to grab your attention, and they’ll do pretty much anything to get it. Up until 2010, one of the techniques they could use was making their commercial WAY louder than the television program you were enjoying. That was until the introduction of the CALM (Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation Act) Act in 2010.

Very broadly, the CALM Act defined loudness standards for television broadcast. A whitepaper entitled “Recommended Practice: Techniques for Establishing and Maintaining Audio Loudness for Digital Television” by the Advanced Television System Committee led to a measurement system called ITU-R BS. 1770 which uses a measurement called “LKFS” to establish loudness levels.

LKFS is an acronym that stands for Loudness, K-weighted, relative to full scale. It’s also known as LUFS. To truly understand how LKFS works, we need to understand how measuring levels in audio works.

What Is LKFS/LUFS?

Most people are familiar with a dB meter: the most common way consumers of digital media (that includes sound) experience the concept of volume. Classically, these are a bar that fills up from top to bottom, or left to right, sometimes with green, then yellow, and then red at the very top to represent clipping or peaking.

A dB Meter in ProTools

dBs don’t measure loudness, not in the way a person experiences it with their ears. Decibel levels like this represent a peak, the current amount of electrical activity in the circuit when it comes to passing audio through it. The scale refers to the amplitude of a signal compared with the maximum a device can handle before clipping occurs.

We get closer to measuring loudness when we use Root Mean Square, or RMS. RMS meters take into account the power of the signal over time. As an example, a snare hit with its high peak and quick decay will measure lower on the RMS scale than a sustained guitar power chord which may not cause a meter to peak in the same way.

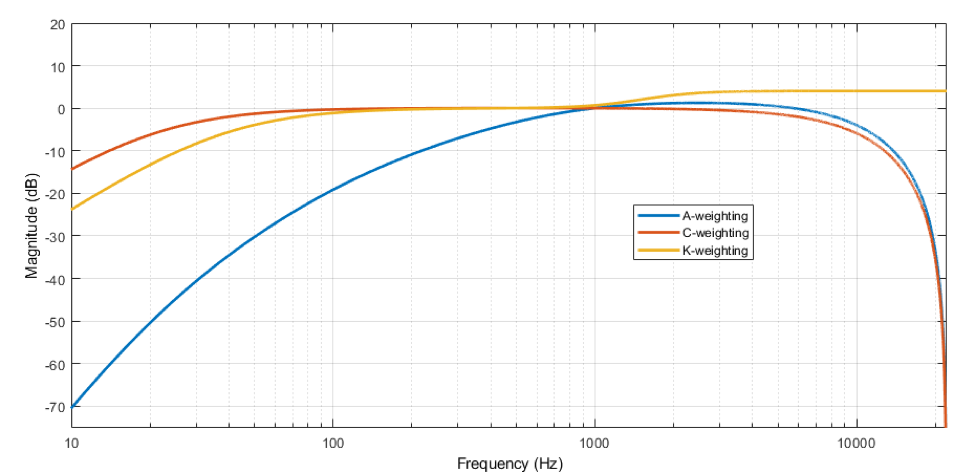

The final piece of the puzzle is the way that our ears respond to different frequencies in the sound spectrum. Even though the human ear is capable, in theory, of picking up frequencies from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, it’s tuned to respond to certain frequencies with greater acuity. To get an accurate loudness measurement for humans, we combine the integrated loudness measurement of RMS with a weighting that’s made for the human ear. This weighting is called K-weighting, and it’s the K in LKFS.

K-weighting over the audible frequency spectrum

To reiterate: LKFS and LUFS are the same thing, but generally the Americans use LKFS while Europeans use LUFS. We’ll use LKFS for the rest of this article.

Why Care About LKFS?

Now that we know what LKFS is and why LFKS is, next up is: why should we care?

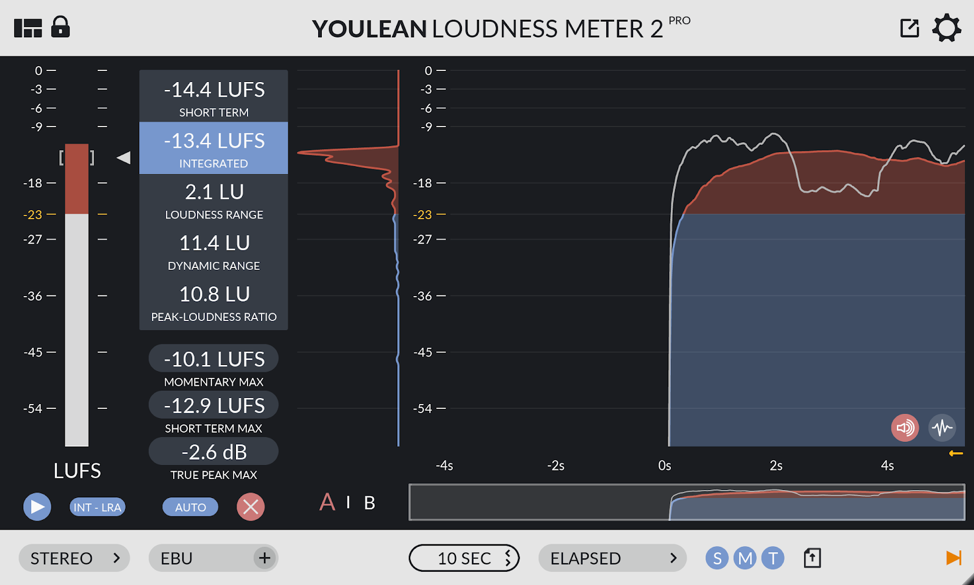

The first application of these standards is broadcast. If you want your video to go on television, including internet television, it has to be mixed with the broadcast LKFS levels. Using meters made for this kind of thing, like iZotope Insight, Youlean Loudness Meter, or the TC Electronics Clarity, we can see that both ATSC A/85 and BS. 1770 call for a Loudness level of -24 and a peak level of -2.

These are the standards you’ll be aiming for for broadcast, but those aren’t the only things you’ll need to take into account. A client might call for a specific dynamic range amount, which means you’ll have to keep an eye on your meters throughout the program you're mixing and use automation, eq, compression, and other tools to make that happen.

The Youlean Loudness Meter 2 Pro

LKFS and LUFS have found homes in places other than broadcast and movies. Spotify and other digital media services have adopted LKFS targets for their content so that the listener will have a more cohesive listening experience when going through a playlist of songs mixed by different engineers.

If you mix your track at -6 LKFS, like Skrillex showed off in his video, Spotify is going to turn your track down to match content with a lower loudness. As of this writing, Spotify shoots for a -14 LKFS level for its content. YouTube has a -13 target, iTunes -16, and Tidal -14.

When I originally started using LKFS in my mixing, I assumed that I should mix and master my music to -13 LKFS, because it was going to be turned down on its final platform anyway. There’s something to be said for not slamming your tracks against a limiter to get them the hottest they can possibly be. That said, different genres are going to sound “better” with different LKFS levels. An EDM track with zero microdynamics is going to be inherently louder than an acoustic track.

As an audio engineer it’s as important to know your genre and what it needs to shine as much as it is to know your final delivery medium.

LUF It or Leave It

Amateur producers and seasoned veterans alike can benefit from using real loudness metering to improve the quality and viability of their mixes. Whether you’re mixing a commercial spot or making lo-fi hip hop in your bedroom, knowing when and how to use LKFS metering will give you an edge to make your project shine.

At VMG Studios, we’re constantly working to improve our methods and tools to make sure any project we do for you looks and sounds the best it can possibly be.

To learn more about the audio trends we expect to see this year, click the image below to download our free Top Creative Trends of 2020 eBook.